Why we need to rethink how we train therapists

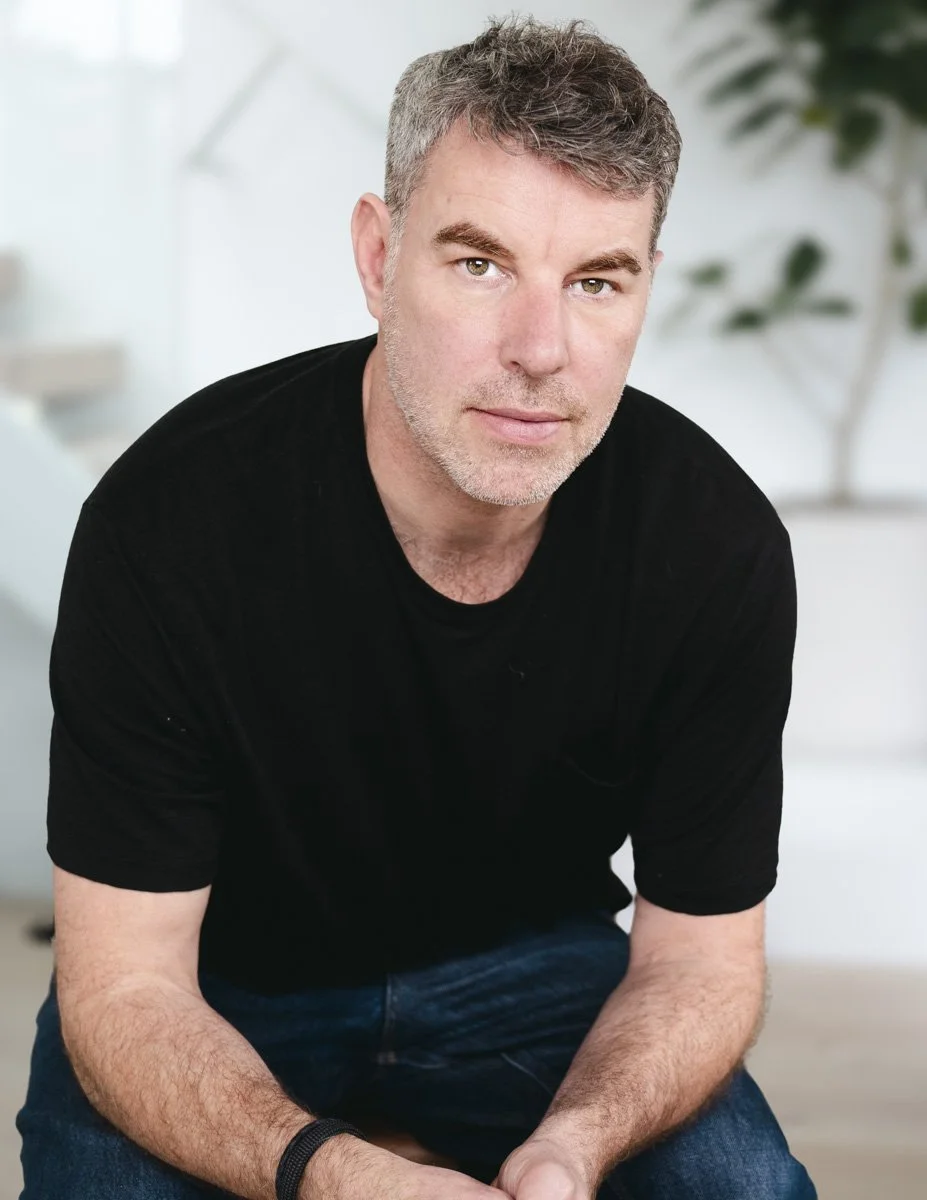

An article by Justin Morrison

Returning to school as a middle-aged student, I experienced some amazing ‘Aha!’ moments, many of which reaffirmed my decision to become a therapist. But one moment stood out from the rest: the day we learned that the relationship isn't just a "nice to have", it is often the most important factor in a client’s healing.

Research consistently shows that the strength of the bond between client and therapist predicts successful outcomes more reliably than almost anything else. We also know that some therapists are simply better at building those bonds and their clients get better faster because of it.

To understand why, think about a mentor in your life who had a lasting impact on you. A teacher, perhaps, or a coach. Now think about the relationship you had with them. It is likely that the bond you shared was deeper than the specific advice they gave. I believe the same dynamic drives therapy: the bond creates the safety that allows a client to let down their defences and fully enter the healing process.

The missing curriculum

Despite this understanding, however, there was no module in our Masters program specifically dedicated to teaching the skills to reliably develop relationships with our clients. This felt like a significant oversight, a missed opportunity to help us reflect on our own relational strengths and weaknesses. We know there are specific qualities we can offer our clients to facilitate the healing process and allow the bond to grow organically. The father of client-centred therapy, Carl Rogers, famously identified these as ‘the necessary and sufficient conditions’ for successful therapy. Rogers identified three core pillars: Empathy (sensing the client's world as if it were your own), Unconditional Positive Regard (holding a non-judgmental stance), and Congruence (being real and authentic).

Rogers himself argued that you cannot learn these qualities from a textbook. They are forms of "tacit knowledge", a kind of embodied know-how that you can only learn by doing. Yet, we often send graduates out into the world with heads full of theory but very little practice in the art of connection.

Therapy is, after all, a practice. And like all practices, the best learning happens not in a lecture hall, but in an apprenticeship. The student must observe a master, attempt the practice under supervision, and repeat the process in an iterative loop of failure, feedback, and growth.

The art of doing less

So, what exactly are we supposed to be practicing? It isn't just "active listening" or nodding politely. The research points to specific behaviors that are actually quite counter-intuitive, not just for therapists, but for anyone trying to be a good listener.

Take, for example, the power of silence. In academia, we call it "Verbal Parsimony," which is just a fancy way of saying: speak less.

We often assume that to help someone, we need to offer brilliant advice or the perfect solution. We feel a pressure to fill the silence. But the data suggests that therapists who use fewer words actually achieve better results.

It sounds easy, right? Just be quiet. But think about the last time a friend or partner told you about a heavy problem. Did you feel that itch to jump in? That anxiety to "fix" it? Resisting that urge, holding the space for someone else to find their own answers, is a muscle that is incredibly hard to build. It requires a level of restraint that you can’t learn from a lecture; you have to practice it over and over, until it becomes your default.

The gift of conflict

Then there is the issue of conflict. What happens when tension or disagreement arise in the therapy room? In the clinical world, we talk about "Rupture and Repair”, and it can be the gateway to a deeper alliance.

Most of us are socialized to be polite, to smooth things over, and to avoid awkwardness at all costs. We treat conflict like a failure of the relationship. But my research highlights a fascinating truth: a "rupture", a break in the bond, isn't the end of the story. In fact, if it is repaired well, the relationship often ends up stronger than it was before. It reminds me of the broken bone that heals stronger than before.

The problem is, when a client gets angry, critical, or withdraws into silence, a new therapist’s instinct is often to panic. We want to make the bad feeling go away. We try to placate, explain, or "fix" the moment to relieve our own anxiety.

Learning to override that instinct, to actually lean into the conflict and explore it without getting defensive, is a profound skill. It turns disharmony into a breakthrough. And again, you can't learn this by reading a book about "conflict resolution." You have to be in the room, feeling the heat, and practicing a new way of responding.

A radical shift in selection

Perhaps the most controversial finding in my research concerns how we select future therapists.

Currently, most graduate programs rely on academic grades and a high-pressure expert panel interview. But here is the problem: studies show that these interviews have little to no predictive value regarding a trainee's future competence. In other words, being charming in an interview does not mean you will be good at helping people heal.

If we really want to improve outcomes for clients, we need to stop selecting based on who can write the best essay. Instead, we should be assessing for innate relational skills using evidence-based tools that measure things like trait empathy.

As things stand, our systems favor those who can jump through academic hoops. This inevitably excludes whole swaths of potentially excellent therapists who are relationally gifted, but perhaps not academically "perfect." And that is a loss for everyone.

The bottom line

Ultimately, rethinking how we train therapists isn't just about changing a syllabus or tweaking an admissions policy. It is about honoring the human bravery it takes to go to therapy.

When a client walks into a therapy room, often in a state of deep vulnerability, they aren't looking for a technician. They aren't checking the therapist’s GPA. They are looking for a human being who can hold their pain without flinching, who can sit in the silence without rushing to fix it, and who can build a bond strong enough to weather the storm.

We know these skills are what matter most. It is time we started training for them.

About the Author: Justin Morrison, MC, MEng

Justin is an associate at the Vancouver Therapy Collective. His approach is client-centered and focused on deeply understanding the inner experience of people who are struggling. Justin’s innate curiosity is reflected in his approach to counselling, where exploration is facilitated by thoughtful questions and reflections. He holds the therapeutic relationship in the highest regard, understanding that clients who feel a true connection in the therapy room tend to have better outcomes.